Home Seminal Contributions to Cytometry Wallace H. Coulter

Wallace H. Coulter

Wallace Henry Coulter was an engineer, inventor, entrepreneur and visionary. He was co-founder and Chairman of Coulter® Corporation, a worldwide medical diagnostics company headquartered in Miami, Florida. The two great passions of his life were applying engineering principles to scientific research, and embracing the diversity of world cultures. The first passion led him to invent the Coulter Principle,™ the reference method for counting and sizing microscopic particles suspended in a fluid.

This invention served as the cornerstone for automating the labor intensive process of counting and testing blood. With his vision and tenacity, Wallace Coulter, was a founding father in the field of laboratory hematology, the science and study of blood. His global viewpoint and passion for world cultures inspired him to establish over twenty international subsidiaries. He recognized that it was imperative to employ locally based staff to service his customers before this became standard business strategy.

Wallace Coulter’s One Technical Paper

With Introduction by Marshall Don. Graham

Wallace, born in February, 1913, spent his early years in McGehee, Arkansas, a small town near Little Rock. Wallace always had an inquisitive mind. At age three, he was fascinated with numbers and gadgets. When offered a bicycle for his eleventh birthday, he asked instead for his first radio kit. He attended his first year of college at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri; however, his interest in electronics led him to transfer to the Georgia Institute of Technology for his second and third years of study.

Wallace at age 3

This was the early 1930s, and due to the Great Depression, he was unable to complete his education. Wallace’s interest in electronics manifested itself in a variety of unconventional jobs. For example, he worked for WNDR in Memphis, TN, filling in as a radio announcer, maintaining the equipment and conducting some of the earliest experiments on mobile communications.

Wallace’s Far East Adventures

In 1935, he joined General Electric X-Ray as a sales and service engineer in the Chicago area servicing medical equipment. This work familiarized Wallace with the testing procedures in the hospital laboratory. When an opportunity to cover the Far East became available, he seized the chance to live and work abroad. The practice of employing expatriates by US companies was not commonplace before World War II. During the next twenty-four months, Wallace was based in three areas servicing the entire Far East: Manila, Shanghai and Singapore. He wrote many letters home to his parents, detailing his adventures and his love of the tropical climate, the food and the cultures.

Wallace’s personal photo, Shanghai in the 1940’s

Wallace first went to the Philippines, where the local GE Office was manned by technicians from many countries. He admired the lush landscape and varied tropical fruits. In his free time, he visited the open air markets. This experience fostered his love of tropical fruits. Later in life, he maintained a tropical fruit farm with lychee, longan, carambola and more than 20 varieties of mangoes.

After six months in Manila, Wallace was asked to make sales and service calls in the more remote regions of the territory. He traveled to Hong Kong, Macao, Canton, finally settling in Shanghai for six months. He became fascinated with Chinese history, art and culture. He admired the jade carvings of all colors, shapes and sizes, but mostly loved figurines of people and animals. He maintained this interest in Chinese art throughout his life. He began collecting jade and his collection was seen covering every surface in his office; he never tired of sharing their beauty.

Wallace sharing his jade collection

Wallace transferred to Singapore where he remained until the Japanese threatened the city in late 1941. With tensions rising, Wallace tried booking his departure on one of the passenger ships leaving the country, but failed. As the Japanese began bombing the city, he found a small cargo boat bound for India and left under cover of darkness in December. After a few weeks in India, Wallace realized that returning to the States through Europe was impossible. He chose a more circuitous route home, making his way through Africa and South America. It took him nearly 12 months, finally returning to the US at Christmas, 1942. Wallace’s sojourn in the Far East and his long journey home traversing four continents was a transformational experience for a young man from small-town America. It forever influenced his values, both professionally and personally.

An Elegant Idea Becomes a Company

After the War, Wallace worked for several electronics companies, including Raytheon and Mittleman Electronics in Chicago. He maintained a laboratory at home to work on promising ideas and projects. One such project was for the Department of Naval Research, where Wallace was trying to standardize the size of solid particles in the paint used on US battleships in order to improve its adherence to the hull.

He began tinkering in his garage laboratory in his spare time, experimenting with different applications of optics and electronics. Upon returning to the garage one cold, blustery evening, Wallace was faced with a challenge. The supply of paint for the experiment had frozen while he was out. Not wanting to go back out in the cold, he asked himself, “What substance has a viscosity similar to paint and is readily available?” Using his own blood, a needle and some cellophane, the principle of using electronic impedance to count and size microscopic particles suspended in a fluid was invented – the Coulter® Principle.

Remembering his visits to hospitals, where he observed lab workers hunched over microscopes manually counting blood cells smeared on glass, Wallace focused the first application on counting red blood cells. This instrument became known as the Coulter® Counter.™

This simple device increased the sample size of the blood test 100 times than the usual microscope method by counting in excess of 6000 cells per second. Additionally, it decreased the time it took to analyze from 30 minutes to fifteen seconds and reduced the error by a factor of approximately 10 times.

Wallace’s first attempts to patent his invention were turned away by more than one attorney who believed “you cannot patent a hole.” Persistent as always, Wallace finally applied for his first patent in 1949 and it was issued on October 20, 1953. That same year, two prototypes were sent to the National Institutes of Health for evaluation. Shortly after, the NIH published its findings in two key papers, citing improved accuracy and convenience of the Coulter method of counting blood cells. That same year, Wallace publicly disclosed his invention in his one and only technical paper at the National Electronics Conference, “High Speed Automatic Blood Cell Counter and Cell Size Analyzer.”

Wallace and Joe, his brother, at the Corporation’s 35th Anniversary celebration

In 1958, Wallace and his brother, Joseph Coulter, Jr., founded Coulter Electronics to manufacture, market and distribute their Coulter Counters. From the beginning, this was a family company, with Joseph, Sr. serving as secretary-treasurer. Wallace and Joe, Jr. built the early models, loaded them in their cars and personally sold each unit. In 1959, to protect the patent rights in Europe, subsidiaries in the United Kingdom and France were established. The Coulter brothers relocated their growing company to the Miami area in 1961, where they remained for the rest of their lives.

Coulter Corporation Global Locations

Under his tenure as chairman of the Corporation, the company developed into the industry leader in blood cell analysis equipment, employing almost 6,000 people, with over 50,000 instrument installations. The company has spawned entire families of instruments, reagents and controls not just in hematology, but also in flow cytometry, industrial fine particle analysis, and other laboratory diagnostics.

Wallace insisted that the company control the entire supply chain: research and development, manufacturing, distribution, sales, financing, training and after-market service and support. In fact, Wallace’s vision is illustrated by the fact that Coulter Corporation was the only diagnostics company to support its instrumentation with the required reagents and quality control materials to operate the full system.

Wallace visiting manufacturing in the early years

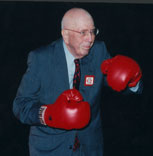

Wallace donned boxing gloves and coached his sales force on his personal “Rule of a Good Salesman.”

When the pressure from competitors increased in the mid-1990s, Wallace donned boxing gloves and coached his sales force on his personal “Rule of a good salesman – List the positives and concentrate on them and after you make the sale, service the needs of your customer the best you can. Do this and you will build a loyal customer base that will stay with you in the hard times.”

The Coulter Principle is responsible for the current practice of hematology laboratory medicine. The complete blood count or “CBC” is the most commonly ordered diagnostic tests worldwide. Today, ninety-eight percent of CBCs are performed on instruments using the Coulter Principle.

In fact, the Coulter Principle touches everyone’s life in some manner: having a blood test, painting your house, drinking a glass of beer or wine, eating a bar of chocolate, swallowing a pill or applying cosmetics. The use of the Coulter Principle modernized industry by establishing a method for quality control and standardization for the particles used in each of these products. It is also critical to space exploration; NASA utilizes it in testing the purity of its rocket fuel. The impact of the Coulter Principle to the medical, pharmaceutical, biotechnology, food, beverage and consumer industries is immeasurable.

Wallace continued to focus the resources of the company on advancing cellular analysis. Coulter Corporation was a pioneer in the development of monoclonal antibodies and flow cytometry, the technology to assay them. These technologies are used in the characterization and treatment of cancer, leukemia and infectious diseases. The B-1 antibody (anti-CD20), marketed as Bexxar, developed under his guidance is proving to be a revolutionary treatment for non-Hodgkin’s small cell lymphoma. This therapy provides hundreds of patients with hope and an improved quality of life, true to his company’s mission of “Science Serving Humanity.” As a result of this continued expansion into “cutting edge” technologies, by the 1990’s, Coulter Corporation was one of the largest privately owned diagnostic companies in the world. In October 1997, Coulter Corporation was acquired by Beckman Instruments, Inc., and the company is now known as Beckman Coulter, Inc. (BEC), a New York stock exchange listed global provider of diagnostic systems and consumables. The Coulter Corporation will always be remembered for placing its customers’ interests ahead of all operational and financial considerations, for its’ strong investment into research, development, and for delivery of innovative products to improve human healthcare.

On the Personal Side

Wallace Coulter was a very private person who sought no public acclaim, yet his accomplishments are numerous. He received 82 patents, many of which were issued to him for discoveries made late in his life. In 1960, Wallace Coulter was awarded the highly prestigious John Scott Award for Scientific Achievement. This award, established in 1816 for “ingenious men and women,” is given to inventors whose innovations have had a revolutionary effect on mankind.

Mr. Coulter joined the likes of his childhood heroes, Thomas Edison, Marie Curie, Jonas Salk and Guglielmo Marconi, in receiving this award. He continued to receive many other awards from business, industry and academia.

He received honorary doctorates from Westminster College, Clarkson College, the University of Miami and Barry University. He was honored with the IEEE Morris E. Leeds Award, Florida Industrialist of the Year, and the M.D. Buyline SAMME Lifetime Achievement Award. Although he was not a physician or hematologist, Wallace is the only person to receive the American Society of Hematology Distinguished Service Award for his enormous contribution to the field of hematology. His was the recipient of the Association of Clinical Scientist’s Gold Headed Cane Award and a Fellow of the American Institute of Medical and Biological Engineering (AIMBE). In 1998, he was inducted into the National Academy of Engineering.

Although Wallace Coulter received much critical acclaim over the years for his contributions to healthcare and industry, he shunned publicity and personal limelight. For Wallace, the accomplishment was important and not the accolades. He lived modestly and invested all of the company’s profits back into research and development. Wallace was a compassionate man who always encouraged his employees to dream and do their best. Wallace remained single his entire life; his company and its employees became his extended family. He personally helped many employees, including providing loans and sponsorships. As an example, he funded an employee’s bone marrow transplant while this technique was still very experimental and not covered by the company’s health insurance. Upon the sale of Coulter Corporation, he ensured that his family of employees was “taken care of” by setting aside a total fund of $100 million to be paid to each and every employee around the world based on their years of service.

Wallace Coulter passed away in August, 1998. As a pioneer of the diagnostic industry he leaves behind a legacy of his achievements, including critical advancements in diagnosis and treatment of disease, a dynamic corporation that will continue to innovate in health care, as well as colleagues, associates, friends and family who were inspired by his influence. His fame and accomplishments continue to be recognized. In 2004, Wallace was posthumously inducted into the National Inventor’s Hall of Fame.

- The Wallace H. Coulter Foundation

- For online version and additional links please visit http://whcf.org/WHCF WallaceHCoulter.htm