Mobiles in Malawi

Using a donated laptop, 100 recycled cell phones, and a copy of FrontlineSMS, Josh Nesbit set up an SMS-based communications network for a rural hospital and its community health workers (CHWs). The network allows the hospital to respond to requests for emergency medical care, track patients, record HIV and TB drug adherence, stay updated on patient status, mobilize remote communities for outreach testing, provide instant drug dosage/usage information, and connect HIV/AIDS support group members.

- Implementing the project and impact on patient care and hospital operations

- Tuberculosis, Meet FrontlineSMS

- SMS for Patient Care, in its Truest Form

- Antiretroviral Texting

- A Guide to Building an SMS Network into a Rural Healthcare System

Healthcare challenges

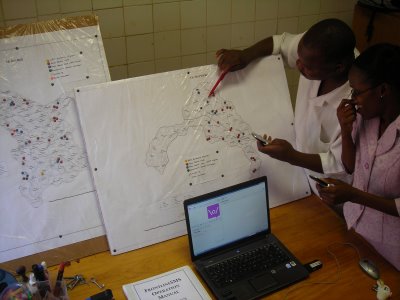

In 2008, FrontlineSMS was implemented as a central SMS hub for a rural hospital in Namitete, Malawi. Located 60 km from Lilongwe, St. Gabriel’s Hospital serves 250,000 Malawians spread over a catchment area 100 miles in radius. The vast majority of the people the hospital serves are subsistence farmers, living on under $1 a day.

The catchment area has an HIV prevalence rate of 15% combined with widespread malnutrition, diarrhea, multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), and other opportunistic infections. Three medical officers are employed at St. Gabriel’s, a physician-to-patient ratio of 1:80,000.

The hospital has enrolled over 600 volunteers to act as community health workers (CHWs) in their respective villages. Many of the volunteers are active members of the HIV-positive community, and were recruited through the hospital’s antiretroviral therapy (ART) program.

When one ART monitor, Benedict Mgabe, was asked why he started volunteering, he replied, “I began when I saw my relatives and friends who were suffering from HIV and AIDS. I took it very personally; I knew I must get involved in curbing this epidemic.”

A need for a true community health network

Distance presents an often-insurmountable obstacle for patients seeking care at St. Gabriel’s. Many patients walk up to 100 miles to the hospital; those with more resources ride bicycles or oxcarts. In order to report patient adherence, ask for medical advice, or request medical care for remote clients, CHWs had to travel similar distances to the hospital’s doors.

The most motivated of the CHWs kept their own patient records, and journeyed to the hospital every few months. Their activities effectively isolated by distance, the impact of the volunteers’ work was restricted to their communities and disconnected from the centralized medical resources at the hospital – their potential role delivering healthcare stifled by disjunction.

- For more stories, background, and implementation information, please visit Josh’s blog at http://www.jopsa.org/

- In February 2009, FrontlineSMS:Medic was launched to extend the capabilities of this software and bring it to health centers across several continents. Please visit http://medic.frontlinesms.com/ for the latest information.

- You can reach Josh via email at josh.nesbit@jopsa.org